[Japanese follows English 英語の後に日本語が続きます]

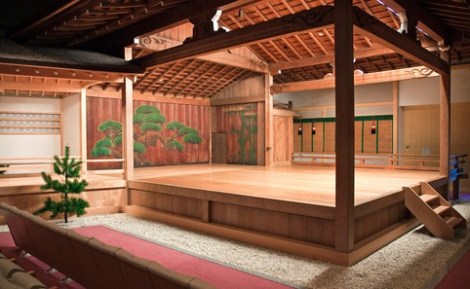

On August 25, 2024, I performed the nō Funa Benkei at the Kongō Nō Theatre in Kyoto. This was my second time performing a full nō play—the first was Kiyotsune back in 2013—and my first time since obtaining the shihan (instructor) license. I have been encouraged to share some thoughts about this experience.

First, I spent a year preparing for this performance, working step by step, block by block, following the regular practice schedule which, in my case, means two practice sessions with my teacher, Udaka Tatsushige, per month. Although numerous amateurs have short classes, I am lucky enough to train for up to two hours per session. In addition to this there is individual practice, which may take place anywhere, in the car (I chant a lot when I drive), at home, but also borrowing our practice space, or even renting a full theatre hall (as I did in Otsu, near Miidera). These individual sessions increased as the performance date approached. I started with the chant, then moved on to the dances, and finally incorporated the dialogue. This gradual process was very helpful, giving me peace of mind as the performance day approached. By the time I was ready to perform, I didn’t feel overwhelmed or stressed. Instead, I had the space to enjoy the experience.

On the day of the performance, as I watched the others prepare backstage, I felt a deep sense of gratitude for the opportunity to share this moment with them. Even though I did not speak much (the shite is not supposed to be verbal before going on stage), I could feel the energy from everyone around me, especially from my teacher and his younger brother. Seeing them, the direct heirs of my previous teacher, reminded me of the continuity of this tradition, and I felt honored to be a part of it.

A particularly powerful moment was when I stood before the mirror, about to put on the mask. The mask symbolizes so much—the character, the history, the ethos of nō itself. Knowing that the masks I used were carved by my previous teacher, Udaka Michishige, and his daughter made it even more meaningful. As I placed the mask on my face, I had to hold back tears, overwhelmed by the weight of tradition, that is, the personal connection to those who came before me.

During the performance, I had little time to think. My focus was on avoiding mistakes, maintaining my composure, and creating the right shape. For an amateur like me, this alone is a great feat. I concentrated on my breathing, ensuring I had enough breath for my lines, and I listened closely to the other performers and musicians, responding to them as best I could. I felt the power of the other performers, and sensed how they were all deeply engaged in the performance. Their energy fueled me, which made me realize just how vital this collective effort is in creating something truly special. This sense of collaboration is what makes theater such a unique art form. Nō takes this to the extreme, reducing the number of performances just to one single event.

As I stood on stage, I recognized many familiar faces in the audience, which greatly motivated me to do my best. After all, nō is performed for an audience, and knowing that their gaze was on me put me in a good place, even though I felt humbled and somewhat worried, knowing that many important guests were present. I am fortunate enough to collaborate with top scholars of nō theatre, both in Japan and internationally. Performing in front of them was daunting, to say the least. Having the waka sōke, Kongō Tatsunori (the son of the iemoto) as the chorus leader, along with many other respected professionals from the nō arts participating in the performance, made me feel like the one out of place on that stage. However, after many years of practice, I’ve learned to overcome that shyness and accept that I can show them who I am without worrying too much about perfection.

Several people told me they thought the first half (Shizuka Gozen) was particularly good, and I have to agree—I enjoyed that part very much. Both halves of the performance had their own difficulties. Dancing in kinagashi, especially for someone with long legs like mine, is not easy. The costume restricts movement to tiny steps, making it challenging to maintain balance. The second half requires skills that take a longer time to hone. Performing powerful yet clean kata, knowing when to speed up and when to slow down, demands much experience, particularly when wearing a mask and costume. The added difficulty of handling the naginata in this play was something I was concerned about. I worried that I might accidentally strike the musicians with the blade, especially during jumps. Long arms can indeed be dangerous! The mask further complicates things by limiting stereoscopic vision, making it difficult to judge depth—crucial for ensuring the safety of the other cast members. This kind of awareness and control can only be developed through experience on stage with a full cast.

What struck me this time was the contrast between the solitude of preparation and the collaborative energy of the performance. In nō, much of the training is solitary, often just you and your teacher. But when you step onto the stage, it’s a group effort, and the tension created by this transition is essential to the rendition of the play. Had we trained and worked together for months, the performance wouldn’t have had the same intensity or spontaneity.

I was also very happy to share the stage with my student, Nami, who took the role of Yoshitsune. She started from zero and made remarkable progress over the past two and a half years. Witnessing their improvement and development has been incredibly rewarding, and I am deeply grateful for that.

After the performance, I felt surprisingly energized. In contrast to my first performance, where I felt too tired to even think about doing it again, this time I wanted to go back on stage right away and correct my mistakes. There were many, but I felt a strong desire to improve and continue.

When it comes to feedback, my teacher, who is usually very verbal, logical, and analytical during practice, is rather dry after performances. Actually, I appreciate that, because I understand how difficult it is to give feedback and how much weight words can carry. Anyway, his comments were generally positive, and although I was critical of myself, pointing out the things I didn’t do right or should have done better, he tried to turn that into something positive. He emphasized that each accomplishment is just a step toward the continuous path of development. This idea is really important and provides the fuel to keep moving forward.

All in all, I am satisfied with how the performance and the event in general went, and I look forward to my next project. Thank you for reading, and for your support.

Diego Pellecchia

2024年8月25日、京都の金剛能楽堂にて能《船弁慶》を勤めさせて頂きました。今回が私にとって二度目の能の公演であり、師範の免許を取得してから初めての公演となります。この経験について、いくつか思いを共有するよう勧められました。

まず、この公演に向けて一年間準備を進め、一歩一歩、ブロックごとに計画を立てて取り組みました。私の場合、月に二回、師匠の宇髙竜成先生の元でお稽古しています。一回の稽古はおよそ2時間です。おそらく、素人弟子にはたっぷりの時間を頂いていると思います。

これに加えて、自己練習も行いました。車の中(運転中によく謡います)、自宅、あるいは稽古場を借りて、さらには大津の三井寺近くにある伝統芸能会館を丸ごと借り切ることもありました。公演が近づくにつれて、これらの自習の頻度は増えました。まずは謡から始め、その後舞へと移り、最後にセリフ(脇とのやり取りなど)を組み込みました。この段階的なプロセスは非常によくて、公演の日が近づくと安心感が得られました。公演の準備が整った時には、圧倒されたり、ストレスを感じたりすることはなく、むしろその経験を楽しむ余裕が少しでもありました。

公演当日、楽屋で他の出演者たちが準備をしているのを見ながら、この瞬間を共有できることに深い感謝の念を抱きました。あまり言葉を交わしませんでしたが(シテは舞台に出る直前にあまり喋らないとされています)、周囲の皆さん、特に先生とその弟さん(徳成先生)からのエネルギーを感じました。彼らは私の前の師匠(通成先生)の直接の後継者であり、伝統の継承を目の当たりにして、この一部となれたことを光栄に思いました。

特に強く印象に残ったのは、面をつける直前に鏡の前に立った瞬間です。面は、キャラクターや歴史、能そのものの精神を象徴しているものであると思います。今回使用した面は、道成先生とその娘さん(景子先生)によって制作されたもので、その意味がさらに深まりました。面を顔につけた瞬間、涙をこらえる必要がありました。伝統の重み、つまり私の前にいた人々との個人的なつながりに圧倒されたからです。

公演中は考える時間がほとんどありませんでした。私の焦点は、ミスを避け、落ち着きを保ち、正しい形を作ることにありました。素人として、これだけでも十分に忙しいです。呼吸に集中し、台詞に十分な息を確保し、他の出演者や楽器奏者の声をよく聞き、できる限り応答しました。他の出演者たちの力も感じました。そのエネルギーが私を駆り立て、この集団的な努力が公演の成功にどれほど重要であるかを実感しました。このコラボレーションの感覚が、演劇を独自の芸術形式にしているのです。能はそれを極限まで追求し、上演回数を一度だけのイベントに絞っています。

舞台に立っていると、観客席に多くの馴染みのある顔を見つけ、それが私を大いに励ましました。能は観客のために演じられるものであり、彼らの視線を感じながら、謙虚でありながらも、重要なゲストが多くいることを意識していました。私は日本国内外の能楽研究の第一人者たちと共に仕事をする幸運に恵まれています。彼らの前で演じるのは、非常に緊張するものでした。若宗家の金剛龍謹(御家元の息子)が地頭を勤め、そして多くの偉い能楽師たちが出演している中で、私だけが舞台で場違いな存在に感じました。しかし、長年の稽古を経て、そのような恥ずかしさを克服し、完璧さにこだわらず、その日、その時の自分を見せることができるようになりました。

何人かの方々から、前半(静御前)が特に良かったと言われ、その通りだと思います。私はその部分を非常に楽しみました。公演の前半と後半にはそれぞれ異なる難しさがありました。特に足の長い私にとって、唐織の着流での舞は簡単ではありません。装束は動きを小さなステップに制限し、バランスを保つのが難しいです。後半では、面と装束を着けながら、強くかつ清潔な型を演じ、スピードの緩急を知る技術が必要です。この演目では長刀の取り扱いが難しく、特に飛び回しに囃子方に刃が当たらないか心配していました。長い腕は本当に危険です!面はまた、立体視を制限するため、他の出演者の安全を確保するための深度感覚を判断するのが難しいです。このような注意力とコントロールは、フルキャストでの舞台経験を通じてのみ養われるものでしょう。

今回私が感じたのは、準備の孤独さと公演の協力的なエネルギーとの対比です。能では、多くの稽古が個人で行われ、しばしば師匠との二人きりです。しかし、舞台に立つと、それはグループの努力となり、この移行によって生じる緊張が、演劇の重要な要素となります。もし私たちが何ヶ月も一緒に稽古をしていたら、今回の公演の持つ強度や自発性はなかったでしょう。

また、私の大学の教え子である奈美さんが義経役を勤めたことも、とても嬉しいことでした。彼女はゼロから始め、過去二年半で驚くべき進歩を遂げました。彼女の成長と発展を目の当たりにできたことは非常に報われるものであり、私は深く感謝しています。

今回の公演は、驚くほどハイテンションで終わりました。2013年、初めてシテとして能を演じた時、「もう二度とやらない!」と感じましたが、今回はすぐに舞台に戻り、間違いを修正したいと思いました。たくさんのミスがありましたが、改善し続けたいという強い意欲を感じました。

フィードバックについては、普段は稽古中にとても口頭で、論理的かつ分析的な師匠が、舞台の後は割と控えめです。実はそれがありがたく思います。教員として、フィードバックを与えることの難しさと、言葉が持つ重みを理解しているからです。私が自分に対して批判的であり、失敗したこと、もっと良くすべきだったことを指摘した時、師匠はそれを前向きなものに変えようとしてくれました。彼は、すべての達成が発展の継続的な道のりの一歩に過ぎないということを強調しました。この考え方は非常に重要であり、前進し続けるための燃料となりますね。

総じて、私は公演とイベント全体の結果に満足しており、次のプロジェクトが楽しみです。ダラダラと書きましたが、この感想文を読んでいただき、またサポートしていただき、ありがとうございます。これからも何卒よろしくお願い致します!

ディエゴ ペレッキア