I re-post here the article that appeared today on Japan Times online. I consider the work of Rebecca Ogamo Teele as a model for all those who would like to pursue the study of Noh in a serious way. I wish Rebecca-sensei all best for her next performance.

Saturday, June 18, 2011

American woman pours self into noh

By JANE SINGER

Special to The Japan Times

According to Rebecca Ogamo Teele, an American instructor, performer and mask carver for noh, falling asleep is a perfectly respectable response to attending such plays.

In fact, she would almost recommend it.

A noh performance can be likened to a meditative state, with a rhythm forged from drum calls and breath-based vocalizations, she explains. This dreamlike world harkens back to the womb, pulsing with the mother’s heartbeat.

“The rhythms of noh can draw you into a trance state,” Teele says. “You may sleep, but at some point there will be a change in the tension, and you’ll wake naturally.”

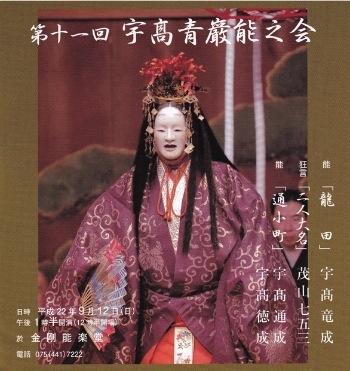

Teele, 62, speaks about noh with familiarity born of 39 years of study, including three decades as an instructor of the classical dramatic and musical art. Her longtime teacher, Michishige Udaka, is a master actor and mask carver in the Kyoto-based Kongo school, one of the largest of the five major noh schools.

Teele’s first exposure to noh was as a child in Kobe, where her father, an educational missionary and scholar of contemporary literature, taught at Kwansei Gakuin University during two stints in Japan totaling nine years that began in 1950.

“My father studied utai (noh chanting) and often brought our family to classical art performances. I can remember when I was very young waking up at noh performances and feeling transported by the otherworldly sounds and the unexpected sight of masked actors,” she says.

After returning to the United States in 1960, Teele fueled her interest in Japanese arts with a fine arts major at Bennington College in Vermont. She returned to Japan in 1971, settling to Kyoto, to learn more about classical theater arts.

She first studied with a mask carver but desired a stronger connection to the plays themselves. Intrigued by Udaka’s insistence on carving the masks for his noh roles himself and his rare openness to teaching women and foreigners, she began to study at the Kongo school.

“Udaka-sensei felt that noh is universal; that if someone trains and has the necessary commitment, they can interpret a role, no matter where they’re from,” she says.

Teele began studying dramatic roles right away, along with daily stretching and vocalization exercises. “In the Kongo School you learn to read notation by parroting the teacher. You start with the simplest, most abstract movements and you learn to listen to and to later interpret the text.”

She gradually mastered the performer’s gliding walk, in which the feet never leave the floor, the elbows are held out and to the side, and fingers are folded in a fist. She demonstrates by gliding across the carpet, with posture held erect but the torso set at a low center of gravity and legs bent. In noh, she says, movement is controlled and usually slow, but it can sometimes unfold explosively fast.

“This posture creates a larger sounding board for your voice and nicely sets off the costume, which often features sleeves twice as long as your arms. Holding your arms this way is physically demanding, calling on stamina and strength,” she explains. The performer typically holds a fan to amplify gestures or mime movements, such as drinking or holding a shield.

“Kabuki has a wonderful flamboyance, but I was attracted by the depth of noh,” she says. “In noh the audience is a kind of witness, called on to participate in the performance. Rather than passively having things laid out for them, they must create something by listening to the chorus and watching the abstract movements, which assume meaning when attached to a text.”

In noh, costumes, dance, utai and poetry help to express overwhelming emotions, such as rage or sorrow, with stories often based on famous historical scenes or Buddhist themes. The main character, the shite, is assisted by an on-stage chorus and a wakikata, or secondary character, who acts as the foil for the shite.

A noh performance typically includes several plays as well as a farcicalkyogen performance.

Over the years, as Teele improved as a noh performer, she began to conceive of a role for herself, she said, “in facilitating communication and understanding among performers and learners.” After nine years of study she became certified as a shihan, or instructor, one of the three foreign instructors whom Udaka has trained. In 1996 she was accepted into the Noh Association under her noh name, Rebecca Ogamo (a play on words, since “kamo” means duck, and a “teal” is a small dabbling duck).

Most noh plays are performed wearing masks, although not all. When performing without a mask the face remains completely emotionless. For the Western actor, the face is the greatest medium of expression, but the use of a mask in noh, rather than serving as a handicap, allows for greater expression of creative energy, Teele says.

“Because the audience is not distracted by the face, you become more aware of the performer’s body and voice. It seems that it would be limiting, but it allows you to access greater powers of expression,” she says. “The mask is the focusing lens for the actor’s energy, and that can be quite transporting.”

She displays a lacquered mask she has carved herself from lightweight Japanese cypress, with straps and linen backing attached. Most masks are carved for specific roles or character types; this one is for Lady Rakujo, the betrayed wife of Prince Genji in the play “Aoi no ue.” The horns and the savage, tooth-bared grimace symbolize a woman transformed by resentment, grief and disillusionment into a demonic spirit, Teele says.

It takes up to a year for Teele to complete a mask like this. “The finest masks have an intense immediacy and can express love, devotion, or grief,” she says. “With an accomplished performer, the mask should seemingly come alive, with the expression changing as the viewing angle changes.”

Teele provides information on noh and teaches both foreign and Japanese students as associate director of the International Noh Institute, a Kyoto-based network of instructors and students affiliated with Michishige Udaka. She says Japanese have no problem accepting a foreign teacher: “Sometimes Japanese prefer a foreigner, since they can ask questions and admit their ignorance of noh without embarrassment.”

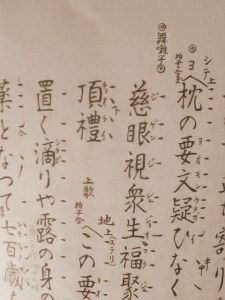

Much of the appeal of noh is in the texts, which are often very short narratives but with compressed layers of meaning. Although many of the most famous noh plays, like “Hagoromo” and “Dojoji,” date back more than five centuries, new plays are being written and performed regularly, many to address contemporary issues.

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the U.S., Udaka pondered the fate of the souls of those who died instantly in mass carnage, leading him to write a play about Hiroshima atomic bomb victims. In the play, “Inori” (“Prayer”), a mother follows the voice of her missing child to the underworld, where a guide escorts her to a site where victims of nuclear and terror attacks reside. Teele accompanied Udaka on a tour of the play to Paris, Dresden and Berlin in 2007, where it was met with enthusiastic, focused audiences, she says.

Teele has appeared on NHK TV, and has lectured and led workshops about noh in Latin America, Europe and New Zealand. In 2003 the Kyoto Prefectural Government recognized her dedication to the dance form by awarding her the Akebono Prize, for women who have contributed greatly to their fields.

She believes that she is the only foreigner to be accepted into the Noh Association, which recognizes professional performers.

She is currently working on a compilation of translated noh plays intended for a general readership, and she has embarked on a project to create smaller-proportioned masks specifically designed for female performers. Last June, she performed as the shitekata, or central character, of the play “Yuki” at the Kongo Noh Theater, a highly abstract role in which, as the spirit of the snow, she materializes before a lost priest and seeks his intercession for finding enlightenment.

“The character is essentially an accumulation of our memories, attachments and illusions,” she says. “In noh, plays like this allow us to experience an awakening of awareness of both the dangers of attachment and the importance of the living things on Earth.”